In her new book Brutus and Other Heroines: Playing Shakespeare’s Roles for Women, acclaimed actor Harriet Walter looks back at her experiences of playing many of Shakespeare’s most famous roles – both female and male – across her varied and distinguished career. Her perceptive and intimate accounts illustrate each play as a whole, and provide invaluable insights for anyone looking to tackle the roles themselves. Here, in a series of extracts from the book, she explores five different roles spanning four decades…

In her new book Brutus and Other Heroines: Playing Shakespeare’s Roles for Women, acclaimed actor Harriet Walter looks back at her experiences of playing many of Shakespeare’s most famous roles – both female and male – across her varied and distinguished career. Her perceptive and intimate accounts illustrate each play as a whole, and provide invaluable insights for anyone looking to tackle the roles themselves. Here, in a series of extracts from the book, she explores five different roles spanning four decades…

OPHELIA – Hamlet, 1981

As Ophelia with Jonathan Pryce (Hamlet); Hamlet, Royal Court Theatre, London, 1980

(© John Haynes/Lebrecht Music & Arts)

The most famous thing about Ophelia is that she goes mad. Richard Eyre, who’d asked me to play Ophelia to Jonathan Pryce’s Hamlet, had given me one major tip as to what he wanted, by telling me what he didn’t want. He did not want ‘mad acting’. I knew what he meant. For Ophelia, her mad scene is an ungoverned artless release; for the actress playing her it can be a chance to show off her repertoire of lolling tongues and rolling eyes, in a fey and affecting aria which is anything but artless. That is the paradox of acting mad. The actor is self-conscious in every sense, while the mad person has lost their hold on self.

Generalised mad acting, being unhinged from any centre, leaves the actor floundering in their own embarrassment. The remedy for me was to find a method in Ophelia’s madness, so that I could root her actions in her motivations (however insane and disordered), just as I would with any other character I was playing. Before playing her I had shared with many others the impression that Ophelia was a bit of a colourless part—that is, until she goes mad. I needed to find a unifying scheme that would contain both the ‘interesting’ mad Ophelia and the ‘boring’ sane Ophelia.

Suppose Ophelia is happily ‘normal’ until her lover rejects her and murders her father. Is that necessarily a cue to go mad? After all, Juliet suffered something of the kind when Romeo killed Tybalt, and although the idea tormented her she did not flip. I started to see that the seeds of Ophelia’s madness had been sown long before the play started, by the workings of a cold, repressive environment on an already susceptible mind. I preferred this theory to the sudden madness-through-grief idea which, together with broken hearts and walking spirits, seemed to belong in the theatre of Henry Irving or a Victorian poem.

VIOLA – Twelfth Night, 1987

As Viola with Donald Sumpter (Orsino); Twelfth Night, Royal Shakespeare Company, 1987

(© Ivan Kyncl/Arena PAL)

I don’t think that Viola is a naturally comic role. Consider her situation:

Viola is shipwrecked, an orphan in a foreign land where no one knows her, and she believes her twin brother and only relative has been drowned. She then falls in love with a man who thinks she’s a boy, and who is infatuated with another woman, and is sent to woo that rival on behalf of the man she loves. Olivia then falls in love with her boy disguise. The audience revels in these complications. Viola does not. Viola isn’t Rosalind, loved and in love, delighting in the freedom of her disguise and knowing she can drop it at any time (in the forest at least).

Viola triggers a lot of comedy but does not crack a lot of jokes. It seems to me that the comedy in Twelfth Night works along a spectrum of self-knowledge with the most self-deceived at one end (Malvolio, Aguecheek), whose idiocy we laugh at, and at the other, the most self-aware, Viola (the only character on stage aware of her real identity), whose wit we laugh with. We laugh at Orsino, who is blinded by love, and at Olivia, who is blind to her vanity in mourning, and at both of them, who are blind to the fact that Cesario is a girl. Sebastian, the ‘drowned’ brother, walks into a chaos he cannot make head or tail of, and we laugh at his confusion. We wryly laugh with Feste, the all-knowing fool, and with Maria, the traditional cunning maid, and we uncomfortably laugh with Belch, who thinks he knows it all and revels in exploiting other people’s weakness.

Although Viola is the most knowing in one way, she is on totally unfamiliar ground (physically and emotionally), and this is a source of comedy for the all-knowing audience.

LADY MACBETH – Macbeth, 1999

As Lady Macbeth with Antony Sher (Macbeth); Macbeth, Royal Shakespeare Company, 1999

(© Jonathan Dockar-Drysdale/RSC)

I suspect that if you were to ask the person-in-the-street what they knew of Lady Macbeth, most who knew anything would say something like ‘She’s the one who persuades her husband to kill the King…’ But I was finding indications in the text that Lady M does not put the idea of killing the King into her husband’s head, it is already there. There is a huge but subtle difference between coercing a totally upright person to commit a crime and working on the wavering will of someone who already wants to commit that crime but fears the consequences. I was not out to clear Lady Macbeth’s name, but I wanted to straighten a few facts.

Shakespeare repeatedly uses the image of planting, and it is an apt one. Macbeth and Lady Macbeth are caught at a moment of ripeness and preparedness for evil. The witches are agents of this evil, and for that reason they do not seek out Banquo, who proves less fertile soil, but Macbeth. Lady Macbeth understands her husband as well as the witches do and builds on the work they have begun. She herself never kills, but if she had let well alone, Macbeth would not have acted. That is the considerable extent of her blame.

I had already scoured the text for any insights into Lady Macbeth as an individual, separate from her husband, but except for the odd ‘most kind hostess’ or ‘fair and noble hostess’ from the King, no one comments on her or throws any light on her character. Nobody seems to know her. She has no confidante. Her world is confined to the castle and its servants, but it was hard for my imagination to people the place or fill it with domestic goings-on. A Lady Macbeth busying herself with the housekeeping or taking tea with a circle of friends just did not ring true. It did not ring true because Shakespeare’s creation only exists within the time-frame of the play. It was as though she had visited Shakespeare’s imagination fully formed, giving away no secrets, and therein lies a lot of her power.

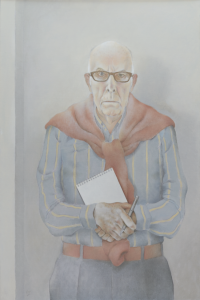

CLEOPATRA – Antony and Cleopatra, 2006

As Cleopatra; Antony and Cleopatra, Royal Shakespeare Company, 2006 (© Pascal Molliere/RSC)

How do you approach playing a woman who reputedly stops the heart and eclipses the reason of every man she meets? Who has Julius Caesar eating out of the palm of her hand? To me Cleopatra was Elizabeth Taylor, Ava Gardner, Mata Hari, the erotic, black-eyed woman on Edwardian postcards, impossible for me to get near. However, once I did my research, I found that nowhere in the play or in any historical account is Cleopatra described as beautiful. In fact any existing images of her make her look rather heavy-browed and long-nosed. Hooray! Yes, but on second thoughts not hooray because that meant she managed to pull the men despite not being beautiful. That means she possessed some indefinable sexual ingredient, the X-factor which you either have or have not got and which is something beyond the art of acting.

What I did have were Shakespeare’s words, and they became my largest sexual attribute. They say the brain is the largest sex organ in the body, and her words were of infinite variety. Playful, grandiose, self-dramatising, switchback, heart-breaking, infuriating and unpredictable. I knew that my best chance of convincing an audience that men might fall at my Cleopatra’s feet would be to get behind those words, the switches of mood, the reach of her imagery, the energy and the emotion to be inferred from her rhythms. And if I could bring all that off the page and on to the stage, I wouldn’t need to fulfil every man’s fantasy with my physique or some ‘X’ ingredient. Getting behind those words would be a tough enough task, but at least it was one that could be worked at, whereas one’s physical attributes are more immutable.

What I also had was the real experience of a woman on the cusp of old age, with all the contradictions that presents. On the one hand still in touch with a youthful energy and physicality, and on the other the consciousness that, as I joked at the time, ‘this may be the last time I play the love interest’. Both Patrick Stewart, who played Antony, and I are fairly fit and athletic—which I am rarely required to demonstrate—so we both used that quality of physical energy and enjoyment wherever we could, and indeed I haven’t had and don’t expect to have another chance to run around the stage barefoot or ever again to leap into a stage lover’s arms.

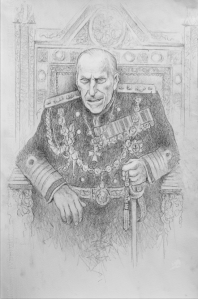

HENRY IV – Henry IV, 2014

As King Henry IV; Henry IV, Donmar Warehouse, 2014 (© Helen Maybanks)

I have to confess to having rather enjoyed strutting and striding and puffing out my chest. I suspect that many men enjoy it too. I have watched those sorts of men all my life, never thinking I would need those observations for an acting job. Since I was very young I have been able to watch someone and imagine myself inside them, moving their limbs, striking their poses and by some strange mechanism, getting an inkling as to their feelings and thoughts. I’m sure everyone has something of this ability, but it is particularly developed in actors. It is hard to explain how it’s done because it is not a systematised process; it is just part of our equipment. It means that we can ‘channel’ someone from real life who matches the character we are playing.

As Henry, I channelled two or three different men (not the men themselves but their acting personae). For obvious reasons I had never had cause to channel Ray Winstone before, but I did now. Another model was Tom Bell; another was the guy from the film A Prophet, Niels Arestrup. If you know any of these actors, you will understand I was not striving to be a lookalike, but somehow, by keeping them in my mind’s eye, I could borrow some useful quality of theirs: the stillness that accompanies physical power, the prowling pace of a man keeping his violence in check, the spread-limbed arrogance of those men on the tube who occupy two seats and leave you squished up in the corner.

It is a bit of a cliché to say it, but in many ways we are all acting. We have all been trained up in our physicality and raised within gender conventions that restrict us. The experiment of being a woman playing a man produced in me a hybrid that surprised me and released me from myself. That is what a lot of actors love best about the whole game—the escape from the limits of the package we are wrapped in. I suspect many non-actors are looking for the same.

These edited extracts are taken from Brutus and Other Heroines: Playing Shakespeare’s Roles for Women by Harriet Walter, out now. To buy your copy for just £10.39, visit the Nick Hern Books website.

These edited extracts are taken from Brutus and Other Heroines: Playing Shakespeare’s Roles for Women by Harriet Walter, out now. To buy your copy for just £10.39, visit the Nick Hern Books website.

Harriet Walter stars in the Donmar Warehouse’s all-female Shakespeare Trilogy – playing Brutus in Julius Caesar, Henry IV in Henry IV, and Prospero in The Tempest – at Kings Cross Theatre, London, until 17 December.

Filed under: Acting Books, Harriet Walter, Shakespeare

This is taken from the Introduction to Lazarus: The Complete Book and Lyrics by David Bowie and Enda Walsh, out now.

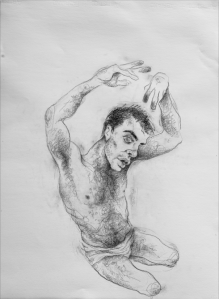

This is taken from the Introduction to Lazarus: The Complete Book and Lyrics by David Bowie and Enda Walsh, out now. The Feldenkrais Method, named after the distinguished scientist and engineer Dr Moshe Feldenkrais, has been used by performers since being adopted by Peter Brook in the 1970s – but it is only now beginning to gain the recognition it deserves. Tapping into the deep relationship between bodily movement and our ways of thinking, feeling and learning, the Method can revolutionise the way actors think about and use their bodies. Here, acting coach and Feldenkrais practitioner Victoria Worsley – author of a new book on the subject, Feldenkrais for Actors – recalls how she first became aware of the Method, and how it ultimately changed her life…

The Feldenkrais Method, named after the distinguished scientist and engineer Dr Moshe Feldenkrais, has been used by performers since being adopted by Peter Brook in the 1970s – but it is only now beginning to gain the recognition it deserves. Tapping into the deep relationship between bodily movement and our ways of thinking, feeling and learning, the Method can revolutionise the way actors think about and use their bodies. Here, acting coach and Feldenkrais practitioner Victoria Worsley – author of a new book on the subject, Feldenkrais for Actors – recalls how she first became aware of the Method, and how it ultimately changed her life…

Because of my acting background, I naturally began to test what actors could do with the Method. I have been exploring and experimenting with it in the course of my work at some wonderful drama schools like Oxford, Rose Bruford and Mountview, as well as workshops at the Actors Centre in London, where I’ve worked alongside the theatre-maker, director and teacher John Wright (who has written the Foreword to my book). My adventures in related fields such as barefoot running and Goju Ryu karate, as well as in the domain of the physiology of emotion, have helped me clarify aspects of the work, and my varied practice with people from many different walks of life has thrown light on how the Method relates to performance. Feldenkrais trainer Dr Frank Wildman told me that Moshe thought his work would be most fully expressed through actors, precisely because they needed to address the use of themselves in every way.

Because of my acting background, I naturally began to test what actors could do with the Method. I have been exploring and experimenting with it in the course of my work at some wonderful drama schools like Oxford, Rose Bruford and Mountview, as well as workshops at the Actors Centre in London, where I’ve worked alongside the theatre-maker, director and teacher John Wright (who has written the Foreword to my book). My adventures in related fields such as barefoot running and Goju Ryu karate, as well as in the domain of the physiology of emotion, have helped me clarify aspects of the work, and my varied practice with people from many different walks of life has thrown light on how the Method relates to performance. Feldenkrais trainer Dr Frank Wildman told me that Moshe thought his work would be most fully expressed through actors, precisely because they needed to address the use of themselves in every way.

Feldenkrais for Actors: How to Do Less and Discover More by Victoria Worsley is out now, published by Nick Hern Books.

Feldenkrais for Actors: How to Do Less and Discover More by Victoria Worsley is out now, published by Nick Hern Books. After a sell-out run at the Edinburgh Fringe in 2016 and winning a Fringe First Award, the extraordinary Us/Them opens at the National Theatre on 16 January. An international co-production between BRONKS, the Brussels-based theatre company for young audiences, and Richard Jordan Productions

After a sell-out run at the Edinburgh Fringe in 2016 and winning a Fringe First Award, the extraordinary Us/Them opens at the National Theatre on 16 January. An international co-production between BRONKS, the Brussels-based theatre company for young audiences, and Richard Jordan Productions

Us/Them by Carly Wijs is published by Nick Hern Books. To buy your copy for just £7.99 (RRP £9.99), visit our website

Us/Them by Carly Wijs is published by Nick Hern Books. To buy your copy for just £7.99 (RRP £9.99), visit our website  After being inspired by a TED Talk about the workings of the teenage brain, Ned Glasier (Artistic Director of

After being inspired by a TED Talk about the workings of the teenage brain, Ned Glasier (Artistic Director of

Company Three’s work is based on a principle of sharing, and we are so happy to be able to share Brainstorm with schools and other young companies. We know from the parents, teachers and other adults who came to see the show how important it is that adults understand what’s going on in the changing teenage brain. And how empowering it can be for teenagers to be the ones to tell them.

Company Three’s work is based on a principle of sharing, and we are so happy to be able to share Brainstorm with schools and other young companies. We know from the parents, teachers and other adults who came to see the show how important it is that adults understand what’s going on in the changing teenage brain. And how empowering it can be for teenagers to be the ones to tell them. Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience: In 2013, I saw a scratch performance of Brainstorm given by twenty-five teenage members of Company Three (then Islington Community Theatre). The group, together with directors Ned Glasier and Emily Lim, had seen my

Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience: In 2013, I saw a scratch performance of Brainstorm given by twenty-five teenage members of Company Three (then Islington Community Theatre). The group, together with directors Ned Glasier and Emily Lim, had seen my  It is important that we find new ways to communicate our scientific discoveries to young people and the general public, and Brainstorm is a perfect example of this. The impact of the play on its audiences at the Royal Albert Hall, Park Theatre, National Theatre and on BBC iPlayer has been profound and long-lasting. The cast have told Kate and me stories of parents rethinking how they understand and interact with their children as a consequence of learning about brain development from the play. We have heard about headteachers who have seen the play and returned to their schools determined to do things differently.

It is important that we find new ways to communicate our scientific discoveries to young people and the general public, and Brainstorm is a perfect example of this. The impact of the play on its audiences at the Royal Albert Hall, Park Theatre, National Theatre and on BBC iPlayer has been profound and long-lasting. The cast have told Kate and me stories of parents rethinking how they understand and interact with their children as a consequence of learning about brain development from the play. We have heard about headteachers who have seen the play and returned to their schools determined to do things differently. Brainstorm by Ned Glasier, Emily Lim and Company Three is out now, published by Nick Hern Books.

Brainstorm by Ned Glasier, Emily Lim and Company Three is out now, published by Nick Hern Books.

The above is taken from the Foreword to

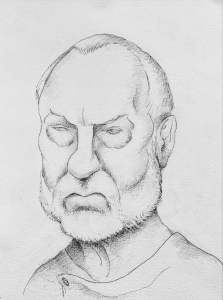

The above is taken from the Foreword to  For his new book Shakespeare On Stage: Volume 2, experienced actor Julian Curry – who himself has appeared in twenty-one of Shakespeare’s plays – spoke to twelve leading colleagues about their experience of participating in landmark Shakespearean productions, each recreating in detail their memorable performance in a major role. Here, read some extracts from the book including Chiwetel Ejiofor on Othello, Zoë Wanamaker on Beatrice, Ian McKellen on Lear, and Fiona Shaw on the Shrew.

For his new book Shakespeare On Stage: Volume 2, experienced actor Julian Curry – who himself has appeared in twenty-one of Shakespeare’s plays – spoke to twelve leading colleagues about their experience of participating in landmark Shakespearean productions, each recreating in detail their memorable performance in a major role. Here, read some extracts from the book including Chiwetel Ejiofor on Othello, Zoë Wanamaker on Beatrice, Ian McKellen on Lear, and Fiona Shaw on the Shrew.

The above is taken from

The above is taken from

The above is an extract from The Voice Exercise Book: A Guide to Healthy and Effective Voice Use by Jeannette Nelson, published by National Theatre Publications, and available now from Nick Hern Books.

The above is an extract from The Voice Exercise Book: A Guide to Healthy and Effective Voice Use by Jeannette Nelson, published by National Theatre Publications, and available now from Nick Hern Books. As a director, Jason Warren has staged immersive theatre productions in a variety of styles and settings – from relocating Shakespeare to a seedy nightclub, to turning school buildings into a quarantine facility for survivors of a widespread plague. Here, he shares his own passion for the form, his hopes for his new book Creating Worlds, aimed at those looking to make this type of work, and reflects on what the term ‘immersive theatre’ actually means…

As a director, Jason Warren has staged immersive theatre productions in a variety of styles and settings – from relocating Shakespeare to a seedy nightclub, to turning school buildings into a quarantine facility for survivors of a widespread plague. Here, he shares his own passion for the form, his hopes for his new book Creating Worlds, aimed at those looking to make this type of work, and reflects on what the term ‘immersive theatre’ actually means…

This is an edited extract from Creating Worlds: How to Make Immersive Theatre by Jason Warren, out now.

This is an edited extract from Creating Worlds: How to Make Immersive Theatre by Jason Warren, out now. Fresh from his acclaimed TV debut Paula on BBC Two, award-winning Irish playwright Conor McPherson’s latest project sees him weave the masterful songs of Nobel Prize laureate Bob Dylan into a poetic, haunting tale of love, loss and obligation set in Minnesota during the Great Depression. As Girl from the North Country premieres at the Old Vic Theatre, London, McPherson reflects on how he found the inspiration for the show, and his deep respect for Bob Dylan’s skills as a musician and writer…

Fresh from his acclaimed TV debut Paula on BBC Two, award-winning Irish playwright Conor McPherson’s latest project sees him weave the masterful songs of Nobel Prize laureate Bob Dylan into a poetic, haunting tale of love, loss and obligation set in Minnesota during the Great Depression. As Girl from the North Country premieres at the Old Vic Theatre, London, McPherson reflects on how he found the inspiration for the show, and his deep respect for Bob Dylan’s skills as a musician and writer…

This introduction is taken from the published script to Girl from the North Country by Conor McPherson, which includes the full text of the play plus the lyrics to all of the Bob Dylan songs featured in the production.

This introduction is taken from the published script to Girl from the North Country by Conor McPherson, which includes the full text of the play plus the lyrics to all of the Bob Dylan songs featured in the production. July 2017 sees the fiftieth anniversary of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, which partially decriminalised sex between men over twenty-one in the privacy of their own homes in England and Wales. When the BBC approached writer, actor and director Mark Gatiss to curate

July 2017 sees the fiftieth anniversary of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, which partially decriminalised sex between men over twenty-one in the privacy of their own homes in England and Wales. When the BBC approached writer, actor and director Mark Gatiss to curate

This interview is taken from

This interview is taken from  Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, in a version by Stuart Paterson

Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, in a version by Stuart Paterson

About a Goth by Tom Wells

About a Goth by Tom Wells

Girls Like That by Evan Placey

Girls Like That by Evan Placey

Ladies’ Day by Amanda Whittington

Ladies’ Day by Amanda Whittington

A round of applause to the fifteen brilliant, brave companies who took NHB-licensed shows to Edinburgh this year!

A round of applause to the fifteen brilliant, brave companies who took NHB-licensed shows to Edinburgh this year! For John Wright, award-winning theatre-maker and teacher, using masks can be liberating for an actor. His new book, Playing the Mask,

For John Wright, award-winning theatre-maker and teacher, using masks can be liberating for an actor. His new book, Playing the Mask,

Playing the Mask: Acting Without Bullshit by John Wright is out now, published by Nick Hern Books.

Playing the Mask: Acting Without Bullshit by John Wright is out now, published by Nick Hern Books. Just when you thought it was safe to go back into the West End…

Just when you thought it was safe to go back into the West End…

This year’s recipient of the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain Award for Outstanding Contribution to Writing is the playwright Caryl Churchill – one of the leading figures in contemporary world theatre, and an NHB author for over thirty years – ‘in honour of her illustrious body of work and a career which has spanned over six decades’.

This year’s recipient of the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain Award for Outstanding Contribution to Writing is the playwright Caryl Churchill – one of the leading figures in contemporary world theatre, and an NHB author for over thirty years – ‘in honour of her illustrious body of work and a career which has spanned over six decades’.

When Steven Slaughter, an English teacher at Rosslyn Academy in Nairobi, Kenya, decided to stage a production of Brainstorm, the acclaimed play about the workings of the teenage brain, he was taking a big risk. The show is designed to be devised by a company of teenagers, putting their own lives and experiences centre-stage. But, as Steven explains, the rewards are immeasurable for everyone concerned…

When Steven Slaughter, an English teacher at Rosslyn Academy in Nairobi, Kenya, decided to stage a production of Brainstorm, the acclaimed play about the workings of the teenage brain, he was taking a big risk. The show is designed to be devised by a company of teenagers, putting their own lives and experiences centre-stage. But, as Steven explains, the rewards are immeasurable for everyone concerned…

Verbatim theatre, fashioned from the actual words

Verbatim theatre, fashioned from the actual words

Telling the Truth: How to Make Verbatim Theatre by Robin Belfield is out now, published by Nick Hern Books.

Telling the Truth: How to Make Verbatim Theatre by Robin Belfield is out now, published by Nick Hern Books.