![]()

VAULT Festival, London’s biggest arts and entertainment festival, is now underway in the Vaults in Waterloo, where it runs until 17 March. With over 400 shows from more than 2,000 artists, featuring the best new writing in theatre and comedy, cabaret, immersive experiences, late night parties and more, there’s something for everyone. And to celebrate the publication of Plays from VAULT 4, an exciting collection of seven of the best plays from the festival, we asked the authors whose work is featured in the anthology to tell us a bit about their play, and what VAULT means to them – plus, at the bottom, a few handy tips on what to see at this year’s festival…

![]() Maud Dromgoole on her play 3 Billion Seconds, 6–10 March:

Maud Dromgoole on her play 3 Billion Seconds, 6–10 March:

3 Billion Seconds is about two hardcore population activists who advocate having no children until (obviously) they get pregnant themselves. We watch them going to greater and greater extremes, struggling to ‘offset’ keeping the baby.

It comes really from being a member of a fair few zero-waste groups, and observing the sporadic militantism and absolute hypocrisy of trying to be a good person in a confusing world. It’s been a complete nightmare play for me in interrogating my own choices. It’s made me vegetarian which is, you know, good for the cows, but sad for me.

The text isn’t particularly prescriptive and I’m very lucky to have a director I trust implicitly. I’m really excited to see what Beth [Bethany Pitts] makes with it, and I hope people will come see it at VAULT.

![]()

![]() Nathan Lucky Wood on his play Alcatraz, 27 Feb–3 March:

Nathan Lucky Wood on his play Alcatraz, 27 Feb–3 March:

Alcatraz is the story of a little girl who breaks into a nursing home to bust her Granny out for Christmas. It’s about finding room for love in big institutions, and the meaning of Christmas, and the meaning of Clint Eastwood.

It started life as a short play for The Miniaturists. I had an idea for a sort of gender-swapped Don Quixote set in modern London. I thought I could write a play where a woman with dementia wanders through London misinterpreting everything she sees, and her granddaughter goes with her, not realising she has dementia. Don Quixote became Donna Quexis and Sancho became Sandy, which I thought was quite clever. Then I sat down to write the play and by the time I had finished, something very different had emerged, and it had nothing to do with Don Quixote except the names. At the time I’d been stuck on a very serious, important play about whistleblowing in the NHS, and Alcatraz seemed to absorb all those themes and ideas. But at heart it’s about a child trying to repair a broken family. Which seems to end up being the subject of every play I write, whether I want it to or not.

It’s a huge privilege to come back to VAULT Festival. It’s an incredible place with an incredible atmosphere, and a fantastic, supportive team behind it. And the venues have so much atmosphere. I’m really excited to see Alcatraz in the Cavern – it’s been my favourite venue here for years and it’s just perfect for the play.

![]()

![]() Margaret Perry on her play Collapsible, 13–17 February:

Margaret Perry on her play Collapsible, 13–17 February:

Collapsible is a play set inside the brain of an unemployed and isolated woman who increasingly feels she is not a person who exists. Interviewing for job after job, she starts to run out of ways to describe herself, and so she decides to make a list, crowd-sourced from the people who know her. Or used to know her. But as the list grows, she soon finds that words on a page aren’t enough to cling to. It’s a monologue about work, self, and trying to wade out of the dark.

The play came from a few different places. When I first moved to London almost five years ago, I was unemployed for three horrible months. Collapsible is partly an exorcism of that time in my life and an interrogation of the damaging way in which our neoliberal capitalist society has intrinsically linked who we are to what we do. I also wanted to explore the tunnel-vision solipsism of depression and anxiety – the ways we push people away just when we need them the most. And I wanted to write a play from the perspective of a complex, compelling bisexual woman.

I’m SO excited to be at VAULT 2019 making this play with the best collaborators I could ask for. VAULT 2017 and 2018 filled my heart and emptied my pockets and I knew I had to be part of it any chance I got!

![]()

![]() Nabilah Said on her play Inside Voices, 23–27 January:

Nabilah Said on her play Inside Voices, 23–27 January:

Inside Voices is a dark comedy about Muslim women from Singapore. It blends humour with magical realism to confront audiences with a community they rarely see, or think about. The play is highly energetic and playful – with mythology and monsters thrown in – to really reflect the atmosphere and rich cultural diversity of Southeast Asia. The show is presented by an all-Asian and all-female team.

I wrote Inside Voices because I saw nothing in London that reflected my sensibilities as a Southeast Asian. Growing up in Singapore, which is a super-modern country and a former British colony, I have a natural (and sometimes confusing) affinity for British culture, but that love isn’t necessarily reciprocated. A lot of people still wonder why I speak good English. The movie Crazy Rich Asians didn’t help either – it put Singapore on people’s radar but it didn’t portray brown people like me who are also Singaporean.

I am so thrilled to be showing Inside Voices at VAULT 2019. Last year I was a festival assistant and I remember thinking, “Man, I wish I could be part of this”. The festival has a real buzz to it. I value the opportunity to share a little bit of Southeast Asia with London – I honestly don’t think people have seen anything like it here. I suppose it’s a bit of a provocation as well: would you watch a show about a community you probably have never cared about?

![]()

Inside Voices by Nabilah Said (publicity shot and author photo by Erfendi Dhahlan)

![]()

Christopher Adams and Timothy Allsop on their play Open, 23–27 January:

We initially conceived of Open after we’d worked together on another play about a nineteenth-century book collector. Chris had been working with an archive to write the play, and we realised we had an archive of our relationship. All our emails, Facebook posts and Guardian Soulmates messages had formed part of material we had handed to the Home Office when Chris was processing his Leave to Remain. This is what began our discussion about doing a show about our relationship, the focus on the ‘open’ aspect came afterwards.

It was an exciting but also complex process of engaging with the timeline of our relationship and working out a narrative structure through which to explore a modern-day romance. When researching we found amazing statistics about how many gay men are in open relationships (40–50%) and yet how few people talk about it openly. There were also lots of different rules that worked for different couples. We found this a useful focus point for the show.

We also interviewed some of our former lovers and friends and used that material in the show. The result was a moving patchwork of voices and experiences which helped to people the stage alongside our own story.

The responses from the audiences have been overwhelmingly positive, with most people connecting with its humour and honesty. We were also amazed by the diversity of the audience and felt the play spoke to all kinds of people. We hope there will be a future life for the piece and fully enjoyed our time at VAULT. It’s also been wonderful to be published in the Nick Hern Books collection.

![]()

Timothy Allsop and Christopher Adams in their play Open

![]()

Dylan Coburn Gray and Claire O’Reilly of MALAPROP Theatre on their play JERICHO, 6–10 February:

Dylan Coburn Gray: JERICHO is a play about the world right now. It’s about a young journalist struggling to get by, writing about things she doesn’t care about and worrying whether writing about things she cared about would be any more meaningful. It’s about professional wrestling, and how it’s like contemporary politics in more ways than you might think. It’s about plausibility, the danger of myths, Roland Barthes and RuPaul, and whether there’s any point even trying to get a pension as well as paying rent if the world’s just going to go on fire before any of us get old.

Jericho is the oldest city. It has a protective wall around it. Chris Jericho’s signature move is named after that wall. Wrestling has always been more about what feels true, rather than what is true. From that little constellation of ideas, the show grew. Its heart is interrogating our sentimentalities about the past and how they lead us to interpret the present.

I think we started off knowing we wanted to make something that would approach the present obliquely. The news cycle right now is such that we spend all our time in our political fury refractory period; you can only get so angry about so many things, and beyond that current events just hurt us with no change in motivation or insight. We didn’t want to just tell people more horrible stuff, we wanted to encourage a reappraisal of the horrible stuff we all already know. Or something like that.

Claire O’Reilly: Having had a blast in Edinburgh for the last two years, bringing work to the UK [MALAPROP is a Dublin-based collective] has so far been a pleasant experience for us (one I’m probably jinxing as I type, go me). It’s exciting to open the conversation out beyond our regular audience, particularly now that we’re no longer complete strangers to the British landscape. That said, being part of VAULT 2019 feels particularly special due to the high volume of Irish work on offer. This is owed in no small part to fellow Irishwoman Gill Greer, Head of Theatre and Performance at Vaults, who really put VAULT Festival on the radar of Irish practitioners.

![]()

JERICHO by MALAPROP Theatre (photo by Molly O’Cathain)

![]() Jodi Gray on her play Thrown, 6–10 March:

Jodi Gray on her play Thrown, 6–10 March:

Jill Rutland and Ross Drury from Living Record approached me a while ago with (what I naively thought was) quite a simple, but beautiful, stimulus for a show: When was the moment you knew you were no longer a child? This is what we referred to as the ‘Thrown’ moment (something to do with the impenetrable philosopher Heidegger) – the point at which we’re hurled unceremoniously into adulthood. We all of us have one, though the levels of drama and sometimes trauma vary hugely; everyone I spoke to could pinpoint theirs immediately.

Along with this simple question, they explained that in performance we would be using binaural technology – an on-stage microphone shaped like a human head with a pick-up in each ‘ear’ – and the audience would listen in via wireless headphones. So, the performer breathes into the left ear of the mic, and each audience member can almost feel their own left ear warming up. (Yes, it is eerie – and has ended up feeling a bit like we have direct access to your brain…)

Part of the development of the play involved us collecting testimony from older people (how better to understand how the end of childhood affects a life?), and I was overwhelmed by the stories we heard, the detail and the joy and the pain. Every one was a privilege to hear, and I’m only sorry I couldn’t include all of them*.

So, this simple idea had somehow become The Stuff of Life – much too much to squeeze into the running-time of a show designed to be performed at a festival. I decided to wrangle it through the character of Dr Constance Ellis – a child psychologist searching through her life story for her own, lost, thrown moment amongst those of her former patients.

Jill is a bewitching performer, and she understood Constance immediately, intuitively. (She also makes everything I wrote magical in ways I could never have dared dream for.) With Ross’s profound direction, and Chris Drohan’s otherworldly sound design, Thrown is not an ‘easy’ watch – but we’ve made something that feels exactly like a memory: strange, enigmatic, bittersweet.

It surprised me in the end that this play, developed so collaboratively, should end up being one of the most personal I’ve ever written. In fact, after one of the previews a close friend turned to me, shaking her head but laughing, and said, ‘No wonder you’re like this.’ I still don’t know what the fuck she means.

We’re so chuffed to be bringing Thrown to VAULT Festival after a run at the Edinburgh Fringe, and ahead of our UK tour – it’s such a beacon of awesomeness in the depths of winter and I love the timelessness of being underground. It’s like a lovely nourishing fugue for all us creative folks.

* These interviews are available to watch on the company’s YouTube Channel as part of Living Record’s ongoing online archive of collected testimony called ‘The Record of Living’ – true stories from the end of childhood retold and relived from people all over the country.

![]()

Thrown by Jodi Gray

What to see at VAULT Festival 2019

Just before the festival opened on 23 January, we asked our authors which shows from this year’s programme they were most excited to see. Check out their picks below…

Maud Dromgoole: I’m really looking forward to so many shows at the festival. All the other shows in the Nick Hern Books anthology look brilliant. I also can’t wait to see Hear Me Howl (30 Jan–3 Feb), Queens of Sheba (30 Jan–3 Feb), Fatty Fat Fat (30 Jan–3 Feb), 10 (13–17 Mar), Pufferfish (6–10 Mar),The Last Nine Months (of the rest of our lives) (20–24 Feb), Lola and Jo (8 Feb), Juniper and Jules (23–27 Jan), i will still be whole (when you rip me in half) (27–28 Feb), Essex Girl (30–31 Jan), Lucy Light (13–17 Mar), WORK BITCH (27 Feb–3 Mar) and Cabaret Sauvignon and a Single VAULT Whiskey (24 Jan–8 Mar), which I think has won VAULT on title alone.

Nathan Lucky Wood: There’s so much great stuff on this year it’s hard to know what to recommend, But I’m hugely excited for WOOD by Adam Foster, directed by Grace Duggan (27 Feb–3 Mar). I saw a very early sharing of it last year and it was absolutely astonishing. I’m really excited to see the full-length play.

Margaret Perry: I’m very excited to see all the other plays in the anthology – particularly 3 Billion Seconds (6–10 Mar), Inside Voices (23–27 Jan) and JERICHO (6–10 Feb). I also can’t wait for Dangerous Lenses (23–27 Jan), 17, (23–27 Jan), i will still be whole (when you rip me in half) (27–28 Feb), Juniper and Jules (23–27 Jan), Pufferfish (6–10 Mar), Landscape (1989), (13–14 Feb), bottled. (13–17 Feb),WORK BITCH (27 Feb–3 Mar), Finding Fassbender (15–16 Mar), and The New Writers’ Showcase (17 Mar).

Nabilah Said: I’m excited for Silently Hoping by Ellandar (20–24 Feb) and SALAAM by Sara Aniqah Malik (30 Jan–3 Feb). Both deal with Muslim-related issues in different ways – Silently Hoping tackles being half-Asian and half-British, while SALAAM is a lyrical take on Islamophobia in Britain. I love that there can be three really different plays at the festival talking about being Muslim. It just shows you that there isn’t one way to be Muslim, and it isn’t mutually exclusive with being human, either.

Maeve O’Mahony of MALAPROP Theatre: I can’t wait to see Queens of Sheba (30 Jan–3 Feb), having missed it at Edinburgh Fringe (actually, note to self, book tickets now). There’s also a plethora of Irish work on offer this year. I’m particularly excited about Sickle Moon Production’s Tryst (13–17 Feb), Sunday’s Child’s Get RREEL (6–10 Feb), Joanne McNally’s Bite Me (13–17 Mar), and Nessa Matthews and Eoghan Carrick’s Infinity (6–10 Feb). I’m also REALLY tempted to extend my stay and crash on a couch so I can catch Oisin McKenna’s ADMIN (27–28 Feb) and Margaret Perry’s new play Collapsible (13–17 Feb)!

Jodi Gray: I’m especially looking forward to all the plays in Nick Hern Books’ VAULT collection, particularly 3 Billion Seconds by Maud Dromgoole (6–10 Mar) and Collapsible by Margaret Perry (13–17 Feb), and then BOAR by Lewis Doherty (6 Mar) (you’d be an absolute idiot to miss this, and it’s on for one night only), 10 by Snatchback (13–17 Mar), Vespertilio by Fight and Hope (20–24 Feb), and Tacenda by RedBellyBlack (20–24 Feb).

![]() Plays from VAULT 4, containing seven of the best plays from this year’s festival, is published by Nick Hern Books. To buy your copy for just £13.59 (RRP £16.99), visit our website now.

Plays from VAULT 4, containing seven of the best plays from this year’s festival, is published by Nick Hern Books. To buy your copy for just £13.59 (RRP £16.99), visit our website now.

Collections from previous VAULT Festivals are also available on our website here.

VAULT Festival 2019 runs from 23 January – 17 March at the Vaults, Waterloo, London. Visit the festival website here.

Nick Hern Books is celebrating its thirtieth anniversary in 2018. To mark the occasion, we’ve commissioned interviews with some of our leading authors and playwrights. First up, theatre journalist Al Senter talks to Dame Harriet Walter…

Nick Hern Books is celebrating its thirtieth anniversary in 2018. To mark the occasion, we’ve commissioned interviews with some of our leading authors and playwrights. First up, theatre journalist Al Senter talks to Dame Harriet Walter…

In her professional life, Harriet has a fear of becoming stuck, like a musical instrument that plays the same notes over and over again. In a sense, her ground-breaking work with Phyllida Lloyd enabled her to find a different tune. But she has also challenged herself repeatedly as an author: her book Other People’s Shoes is an elegant analysis of what an actor is and does, while Facing It is a series of reflections on images of older women whose faces and lives have inspired her.

In her professional life, Harriet has a fear of becoming stuck, like a musical instrument that plays the same notes over and over again. In a sense, her ground-breaking work with Phyllida Lloyd enabled her to find a different tune. But she has also challenged herself repeatedly as an author: her book Other People’s Shoes is an elegant analysis of what an actor is and does, while Facing It is a series of reflections on images of older women whose faces and lives have inspired her. Harriet Walter’s Brutus and Other Heroines: Playing Shakespeare’s Roles for Women is published by Nick Hern Books in paperback and ebook formats.

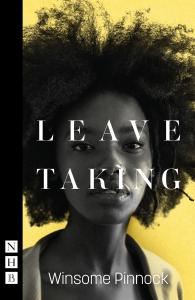

Harriet Walter’s Brutus and Other Heroines: Playing Shakespeare’s Roles for Women is published by Nick Hern Books in paperback and ebook formats. Winsome Pinnock’s play Leave Taking, about a Caribbean family living in North London, is as powerful today as it was when it was first performed in 1987. As a major new production opens at the Bush Theatre in London, the author reveals how she came to write it, and how it was inspired by her own family story…

Winsome Pinnock’s play Leave Taking, about a Caribbean family living in North London, is as powerful today as it was when it was first performed in 1987. As a major new production opens at the Bush Theatre in London, the author reveals how she came to write it, and how it was inspired by her own family story…

Reproduced from the new edition of Leave Taking by Winsome Pinnock, published on 24 May 2018 by Nick Hern Books.

Reproduced from the new edition of Leave Taking by Winsome Pinnock, published on 24 May 2018 by Nick Hern Books. Continuing our series of interviews with our leading authors and playwrights, commissioned to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of Nick Hern Books in 2018,

Continuing our series of interviews with our leading authors and playwrights, commissioned to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of Nick Hern Books in 2018,

Rona Munro’s plays are published by Nick Hern Books, including a new edition of

Rona Munro’s plays are published by Nick Hern Books, including a new edition of  Lucy Kirkwood is a leading playwright whose plays include the hugely acclaimed Chimerica. She spoke to theatre journalist Al Senter as part of our interview series celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of Nick Hern Books in 2018

Lucy Kirkwood is a leading playwright whose plays include the hugely acclaimed Chimerica. She spoke to theatre journalist Al Senter as part of our interview series celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of Nick Hern Books in 2018

Puppetry is an artform with ancient roots, but contemporary applications – and the international success of shows like National Theatre hit War Horse proves that it has lost none of its magic.

Puppetry is an artform with ancient roots, but contemporary applications – and the international success of shows like National Theatre hit War Horse proves that it has lost none of its magic.

Freak by Anna Jordan

Freak by Anna Jordan

How My Light Is Spent by Alan Harris

How My Light Is Spent by Alan Harris Antigone by Sophocles, adapted by Owen McCafferty

Antigone by Sophocles, adapted by Owen McCafferty

Good luck and break a leg to all the brilliant amateur companies taking NHB-licensed shows to the Edinburgh Fringe this year!

Good luck and break a leg to all the brilliant amateur companies taking NHB-licensed shows to the Edinburgh Fringe this year! Jack Thorne is the playwright behind Harry Potter and the Cursed Child and a five-times BAFTA-winning screenwriter. He talked to theatre journalist Al Senter about his abiding love for theatre, while, below, we publish his speech at the Nick Hern Books thirtieth anniversary party at the Royal Court Theatre in July…

Jack Thorne is the playwright behind Harry Potter and the Cursed Child and a five-times BAFTA-winning screenwriter. He talked to theatre journalist Al Senter about his abiding love for theatre, while, below, we publish his speech at the Nick Hern Books thirtieth anniversary party at the Royal Court Theatre in July… Jack took to writing plays, as he says in the extraordinarily revealing Introduction to the first volume of his Collected Plays, ‘as a means of expressing things which I couldn’t say.’ He laments in those pages that ‘I’m a constant idiot in conversation. I always seem to sound either smug or stupid.’ There’s a self-lacerating streak to Jack’s conversation still, even if that period of ‘utter self-hatred and destruction’ now lies in the past. You get the sense that, for him, writing has always been something of a displacement activity.

Jack took to writing plays, as he says in the extraordinarily revealing Introduction to the first volume of his Collected Plays, ‘as a means of expressing things which I couldn’t say.’ He laments in those pages that ‘I’m a constant idiot in conversation. I always seem to sound either smug or stupid.’ There’s a self-lacerating streak to Jack’s conversation still, even if that period of ‘utter self-hatred and destruction’ now lies in the past. You get the sense that, for him, writing has always been something of a displacement activity.

This week saw the tragic passing of playwright and NHB author Stephen Jeffreys. Known for works including hit historical romp The Libertine, he was also a caring and supportive mentor to an entire generation of writers. In this edited introduction from a recently published collection of Stephen’s plays, his wife, Annabel Arden, pays tribute to the life and career of a much-loved figure. Plus, publisher Nick Hern shares a few words on a man he was proud to not only call an author, but a friend

This week saw the tragic passing of playwright and NHB author Stephen Jeffreys. Known for works including hit historical romp The Libertine, he was also a caring and supportive mentor to an entire generation of writers. In this edited introduction from a recently published collection of Stephen’s plays, his wife, Annabel Arden, pays tribute to the life and career of a much-loved figure. Plus, publisher Nick Hern shares a few words on a man he was proud to not only call an author, but a friend

Howard Brenton’s career as a playwright encompasses an extraordinary variety of subjects and many glittering successes, from Pravda and The Romans in Britain to Paul and Never So Good. But, as he

Howard Brenton’s career as a playwright encompasses an extraordinary variety of subjects and many glittering successes, from Pravda and The Romans in Britain to Paul and Never So Good. But, as he

‘With Pravda, something happened that can occur with writers and their characters. We had intended to do a version of Faust, with Andrew the newspaper editor tempted by Le Roux as Mephistopheles; but we fell in love with Lambert in the way that Shakespeare makes audiences complicit with Richard III or Macbeth.’

‘With Pravda, something happened that can occur with writers and their characters. We had intended to do a version of Faust, with Andrew the newspaper editor tempted by Le Roux as Mephistopheles; but we fell in love with Lambert in the way that Shakespeare makes audiences complicit with Richard III or Macbeth.’

Why are Brecht’s theories often so baffling? And are they any use to theatre makers today?

Why are Brecht’s theories often so baffling? And are they any use to theatre makers today?

Theatre that encourages audiences to discover things actively without preaching to them? That seemed exciting, and it was quite different from what I vaguely remembered about Brecht from university. I read more, and realised why so many people didn’t like him. Translated by the esteemed John Willett, Brecht on Theatre was a tough read. And what was meant by that business about turning right or left? I realised it was about showing an audience that a decision was being made. Nothing was inevitable: humans could make the opposite choice at each pivotal moment. A bit like Sliding Doors, that film in which the central character’s life goes down two different paths depending on whether or not she catches a particular train – but with Brecht, the important thing was that the person would decide whether or not to get on the train. A moment of choice, not a whim of fate. A decision with a political, not a sentimental purpose.

Theatre that encourages audiences to discover things actively without preaching to them? That seemed exciting, and it was quite different from what I vaguely remembered about Brecht from university. I read more, and realised why so many people didn’t like him. Translated by the esteemed John Willett, Brecht on Theatre was a tough read. And what was meant by that business about turning right or left? I realised it was about showing an audience that a decision was being made. Nothing was inevitable: humans could make the opposite choice at each pivotal moment. A bit like Sliding Doors, that film in which the central character’s life goes down two different paths depending on whether or not she catches a particular train – but with Brecht, the important thing was that the person would decide whether or not to get on the train. A moment of choice, not a whim of fate. A decision with a political, not a sentimental purpose.

Brecht: A Practical Handbook by David Zoob is out now, published by Nick Hern Books.

Brecht: A Practical Handbook by David Zoob is out now, published by Nick Hern Books. As her latest play Sweat opens at the Donmar Warehouse in London, the double-Pulitzer-winning playwright Lynn Nottage reveals the painful personal encounter that led her to write it, and how her intensive research uncovered truths overlooked by mainstream media…

As her latest play Sweat opens at the Donmar Warehouse in London, the double-Pulitzer-winning playwright Lynn Nottage reveals the painful personal encounter that led her to write it, and how her intensive research uncovered truths overlooked by mainstream media…

Sweat by Lynn Nottage is out now, published in the UK and Ireland by Nick Hern Books.

Sweat by Lynn Nottage is out now, published in the UK and Ireland by Nick Hern Books.

They included the exhilarating debut play from Natasha Gordon,

They included the exhilarating debut play from Natasha Gordon,

Jez Butterworth’s magnificent play

Jez Butterworth’s magnificent play

This year we published Antony Sher’s account, in his own diary entries, paintings and sketches, of his portrayal of King Lear for the RSC.

This year we published Antony Sher’s account, in his own diary entries, paintings and sketches, of his portrayal of King Lear for the RSC.

***Our most-performed play in 2018***

***Our most-performed play in 2018***

Maud Dromgoole on her play

Maud Dromgoole on her play

Nathan Lucky Wood on his play

Nathan Lucky Wood on his play

Margaret Perry on her play

Margaret Perry on her play

Nabilah Said on her play

Nabilah Said on her play

Jodi Gray on her play

Jodi Gray on her play

Plays from VAULT 4, containing seven of the best plays from this year’s festival, is published by Nick Hern Books. To buy your copy for just £13.59 (RRP £16.99), visit our

Plays from VAULT 4, containing seven of the best plays from this year’s festival, is published by Nick Hern Books. To buy your copy for just £13.59 (RRP £16.99), visit our  As Ghost Stories returns to terrify London audiences, and appears in print for the first time, its creators Andy Nyman and Jeremy Dyson explain how they came up with idea, and the inspirations they drew on.

As Ghost Stories returns to terrify London audiences, and appears in print for the first time, its creators Andy Nyman and Jeremy Dyson explain how they came up with idea, and the inspirations they drew on.

That’s why Nick Hern Books has created Multiplay Drama – a new series aiming to bring back to the fore some of the best plays for large casts we’ve read. Offering ten high-quality plays that originated with various drama schools and youth-theatre companies, it provides a selection of ambitious, complex, dramatic and theatrical plays with one common factor: large casts of rich, exciting characters for teenagers and young adults to perform.

That’s why Nick Hern Books has created Multiplay Drama – a new series aiming to bring back to the fore some of the best plays for large casts we’ve read. Offering ten high-quality plays that originated with various drama schools and youth-theatre companies, it provides a selection of ambitious, complex, dramatic and theatrical plays with one common factor: large casts of rich, exciting characters for teenagers and young adults to perform. If your performance group is looking for a play that builds a post-apocalyptic world and focuses on a large group of identifiable characters navigating through a dystopian vision of Britain –

If your performance group is looking for a play that builds a post-apocalyptic world and focuses on a large group of identifiable characters navigating through a dystopian vision of Britain –

In addition to his success as a highly respected writer and teacher, Stephen Jeffreys also spent many years working on a guide to the craft of playwriting, to share his wisdom and experience. That book,

In addition to his success as a highly respected writer and teacher, Stephen Jeffreys also spent many years working on a guide to the craft of playwriting, to share his wisdom and experience. That book,

Bristol-based theatre collective The Wardrobe Ensemble have been winning plaudits and delighting audiences across the UK with their brand of theatrical ingenuity and irreverent humour. As their acclaimed show

Bristol-based theatre collective The Wardrobe Ensemble have been winning plaudits and delighting audiences across the UK with their brand of theatrical ingenuity and irreverent humour. As their acclaimed show

This is an edited extract from material accompanying the playscript in 1972: The Future of Sex, published by Nick Hern Books on 2 May 2019.

This is an edited extract from material accompanying the playscript in 1972: The Future of Sex, published by Nick Hern Books on 2 May 2019. Robert Holman is the playwright most admired by other playwrights. Championed by writers such as Simon Stephens and David Eldridge, his plays – including Making Noise Quietly, Jonah and Otto and A Breakfast of Eels – combine close observation of the way people behave with a thrilling and often fiercely uncompromising mastery of dramatic form. His work is now set to find new audiences, with the film adaptation of Making Noise Quietly showing on cinema screens from this week. Here, alongside the publication of a collection of his early plays, Robert Holman Plays: One, he reflects on his own approach to playwriting, and how each of his plays has been shaped by his own personal circumstances.

Robert Holman is the playwright most admired by other playwrights. Championed by writers such as Simon Stephens and David Eldridge, his plays – including Making Noise Quietly, Jonah and Otto and A Breakfast of Eels – combine close observation of the way people behave with a thrilling and often fiercely uncompromising mastery of dramatic form. His work is now set to find new audiences, with the film adaptation of Making Noise Quietly showing on cinema screens from this week. Here, alongside the publication of a collection of his early plays, Robert Holman Plays: One, he reflects on his own approach to playwriting, and how each of his plays has been shaped by his own personal circumstances.

The above is an edited extract from the introduction to

The above is an edited extract from the introduction to